From Farleys to Chandigarh

These two places could not be more different: the planned city of Chandigarh on a dusty plain in northern India, designed by a group of European modernists and their Indian colleagues, led by Le Corbusier, and an eighteenth-century farmhouse in a tiny village by the South Downs of Sussex.

Farleys House in East Sussex

In that spot in rural Sussex, many of the great artists of the twentieth century came to play at the home of two remarkable characters: the surrealist artist and poet, exhibition curator and biographer Roland Penrose and his fashion model turned photographer turned fearless war correspondent and finally turned gourmet cook wife, Lee Miller. Henry Moore, Picasso, Max Ernst, Leonora Carrington and Joan Miró could have been sat next to you at the dining table to eat one of Lee Miller’s spectacular surrealist dinners. But it was not only artists who visited. Numbering amongst the guests were another twentieth-century power couple: the architects Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry. And of course, Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry were amongst those European modernists who set off for India in 1951 to design Chandigarh.

Lee Miller’s kitchen at Farleys House where the surrealist dinners were prepared on the stove below their hand painted Picasso tile.

Copyright Lee Miller Archives Photography Tony Tree

During the summer I work a few days per month at Farleys House, Lee Miller and Roland Penrose’s home for the last few decades of their lives, and it is now run as a museum and gallery. Visitors to the house can go on a guided tour and get a glimpse into the lives of these two extraordinarily sociable and talented people, their art collection including works by Man Ray, Picasso, Miró, Alexander Calder and Julian Opie alongside beautiful ethnographic works, folk art and ceramic pieces.

One day I noticed a photograph of Maxwell Fry in a group of people gathered outside the house including Man Ray and Antony Penrose, Lee and Roland’s son. I approached Antony Penrose, to ask him about this contact. He remembers Maxwell Fry as an attentive and kind, softly-spoken man who was a visitor to the house, often with his wife Jane Drew.

From the front: Man Ray, Juliet Browner, Heather the dog, Peter Gregory, Joyce Reeves, Roland Penrose and John Funnell, Maxwell Fry, Patsy Murray and Antony Penrose outside Farleys House in 1957 taken by Lee Miller

Copyright: Lee Miller Archives

The relationship between Maxwell Fry, Jane Drew, Roland Penrose, and Lee Miller was not simply a social connection between avant-garde peers, but an expression of a shared cultural ambition. Penrose and Miller brought a surrealist legacy rooted in disruption and psychic liberation. Drew and Fry, meanwhile, brought their modernist architecture to bear on the social needs of the decolonizing world. Their lives overlapped at crucial points, geographically and philosophically in Farleys House and at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London.

Farleys House and the Surrealist Imagination

Farleys House was no ordinary country home. Here, Penrose and Miller hosted an international constellation of artists who were reshaping the visual and intellectual landscape of the 20th century. Surrealism, for Penrose, was a philosophy as much as an aesthetic, and Miller, ever the reinventor, embodied its fluidity. Their parties and dinners, their extraordinary décor, and Miller’s notorious surrealist culinary experiments were themselves works of art. Drew and Fry, regular guests, found in this environment a release from the strictures of post-war planning and bureaucratic architectural practice.

The dining room at Farleys House with the mural painted by Sir Roland Penrose.

Copyright Lee Miller Archives Photography Tony Tree

Drew and Fry’s Chandigarh: Modernism with Purpose

Drew and Fry had already proven themselves as pioneers of tropical modernism in West Africa, where they developed architectural solutions tailored to climate and local materials. In India, they brought those lessons to Chandigarh. Unlike Le Corbusier, who was in charge of the design of the monumental buildings, Drew and Fry worked closely with Indian collaborators on housing, infrastructure, and neighbourhood planning.

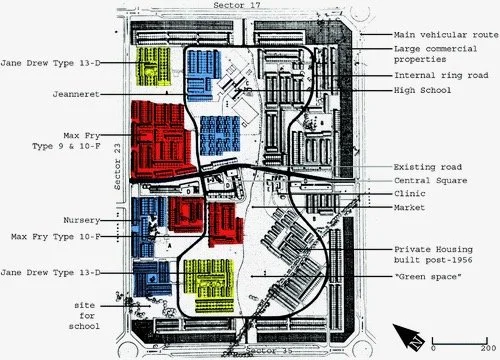

In Chandigarh, they applied principles from British and American neighbourhood planning, especially the Garden City Movement, to create walkable communities with integrated schools, clinics, and shops. They intended that their designs were not imposed from above but developed through consultations with local workers, traders, and residents — a collaborative modernism informed by anthropology as much as architecture.

Sector 22 as laid out by Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry

Their work challenged prevailing narratives. Fry, who co-founded the MARS Group (the UK counterpart to CIAM – French acronym for the International Congress of Modern Architecture established by Le Corbusier in Switzerland in 1928) and had written influential texts on tropical housing, rejected the cold brutality of concrete modernism and instead embraced regional nuance. His Government Print Office with its curtain glass wall and innovative louvre system, stood apart from Le Corbusier’s immense grand concepts in concrete. For both Fry and Drew, modernism had to respond to people and place.

The aluminium louvre system of the Government Print Office in Chandigarh, one of the first buildings designed by Maxwell Fry in the city

Points of Contact: ICA and the Independent Group

One vital meeting point of the surrealist and modernist circles was the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA), co-founded by Penrose in 1946. The ICA was not just a gallery— it was a laboratory of ideas. Drew and Fry were connected to this milieu, particularly through the Independent Group, which questioned the binaries of high and low culture and embraced a kind of post-war eclecticism. Jane Drew was crucial in making possible the Dover Street gallery space in 1950 which became the first home of the ICA and subsequently the current home on the Mall in 1968. Drew and Fry designed the interior spaces and with others the furniture and fittings for these spaces.

While Fry and Drew were involved in constructing new cities, Penrose and Miller were constructing new ways of seeing. Both couples were responding to war, imperial collapse, and rapid social change by inventing and reinventing modernity. Whether through the prism of surrealism or the grid of city planning, they sought to humanise, reimagine, and rebuild.

Chandigarh as Cultural Project

Chandigarh is often understood through Le Corbusier’s dramatic Capitol Complex, but it was at the smaller scale with Drew’s careful layout and Fry’s neighbourhood-level interventions, that made the city function. Their approach was not to emulate European models, but to negotiate between internationalist ideals and Indian realities. As Fry once said, climate was the ultimate guide in Indian architecture — more influential than tradition or theory.

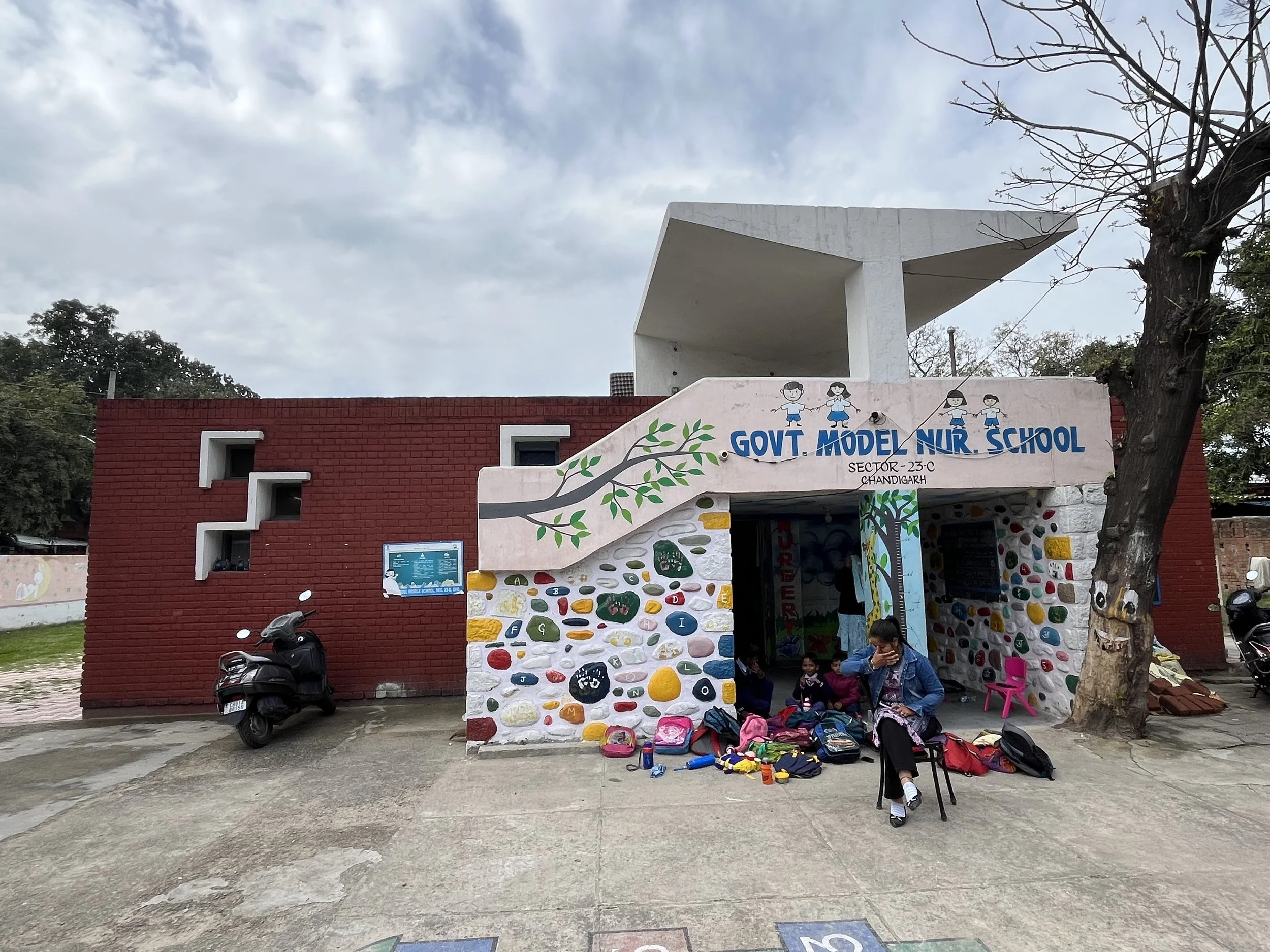

Their cinema, schools, and housing clusters were built with brick, shading, and low-cost materials that could be reproduced, adapted, and inhabited. This was modernism not as monument, but empirical, and socially attuned. Much like the surrealists, Drew and Fry sought to liberate —only their canvas was the built environment.

Chandigarh Junior School

A Shared Legacy of Experimental Living

The legacy of these four figures is not confined to buildings or images, but to the environments — both physical and intellectual — they helped create. Whether through Miller’s lens or Drew’s blueprints, each sought a break from the past and a blueprint for the future. They understood, intuitively and experientially, that modernity was not a style but a method, and often improvisational.

Their meeting points, whether over dinner at Farleys or in ICA debates, were not incidental. They were deliberate exchanges between people who believed that creativity was the engine of progress. The warmth of Miller’s kitchen, the rigour of Fry’s lecture notes, the dream scapes of Penrose’s collages, and the calm geometry of Drew’s housing plans, they all tell part of the same story.

Of course it was not all social progress. When Drew suggested the creation of unisex toilet facilities at the ICA to allow for more exhibition space, Lee Miller stepped in to point out that she did not intend to use toilets that men had pissed all over. And that debate still rages on today.